Groups of people have collective identities, and the identities of the groups that we are a part of have a profound effect over us. There is a new emergent possibility of ‘InterBeing’ and how the field of relatedness can become a living organism of shared communion. Being on the edge – arrow of evolution – is powerful and empowering even though it can be challenging.

Humanity is seeking a new self-understanding, away from the self as a separate entity to the self as intimately intertwined with other people and the entire cosmos. This new integral consciousness includes a new awareness of a new kind of collective – interbeing and interrelationality.

In the introduction of his book, Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell (of Tipping Point and Blink fame) describes the mysterious town of Roseto, Pennsylvania as an example of an outlier.

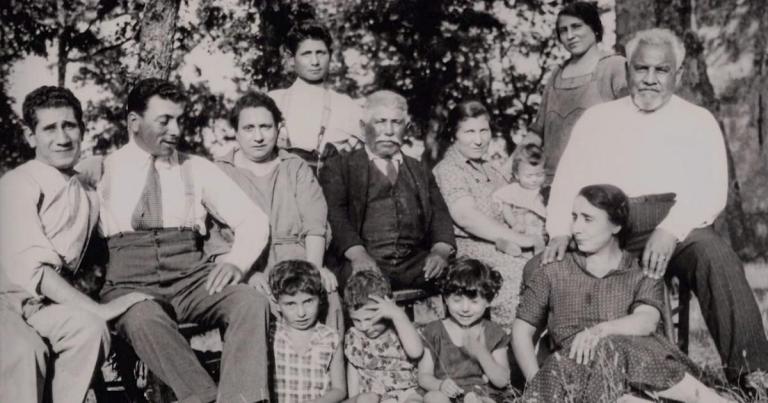

In 1882, a group of men left Roseto Valfortore (Valley of Roses), a town of 1300 located near the Province of Foggia in the Southern Italian region of Puglia and set sail for New York. As described by Gladwell, “For centuries, the paesani of Roseto worked in the marble quarries in the surrounding hills, or cultivated the fields in the terraced valley below, walking four or five miles down the mountain in the morning and then making the long journey back up the hill at night. It was a hard life. The townsfolk were barely literate and desperately poor and without much hope for economic betterment – until word reached Roseto at the end of the nineteenth century of the land of opportunity across the ocean”.

1887, Nicola Rosato, purchased land and built the first house. He had founded the town of Roseto Pennsylvania, naming it for his Italian village.

Roseto became the first 100% Italian borough in the USA. The town was largely settled by immigrants who followed the founders from their native Roseto Valfortore. One group of Rosetans after another packed their bags and headed to Pennsylvania. By 1894, 1200 Rosetans had applied for passports to America, leaving entire streets of their native village abandoned.

According to Gladwell, Roseto Pennsylvania came to life. They built closely clustered houses; they built Our Lady of Mt. Carmel Church, and they named the main street on which it stood Garibaldi Avenue after the hero of Italian Unification. They set up spiritual societies and organized festivals. In every yard they planted gardens, raised pigs and grew grapes for homemade wine. They built schools, parks, a convent, and a cemetery. All the while, they opened family owned shops, bakeries, and restaurants. Everyone fought over bragging rights for the best wine in town. Only Italian was spoken in the early 1900’s – and not just any Italian, but the Foggian dialect. Roseto had become its own self sufficient world and probably would have remained so but for a man named Stewart Wolf.

Wolf was a physician and medical school professor who spent summers on a farm not far from Roseto.

Wolf was approached by a local doctor who told him he had been practicing locally for 17 years and he treated patients from all over the area not just from Roseto. He explained that he rarely found anyone from Roseto under the age of 65 with heart disease – notwithstanding that heart disease in the United States was an epidemic at this time, it being prior to the advent of cholesterol awareness and cholesterol controlling medication.

Wolf, along with a sociologist named Bruhn, conducted a study and invited the entire population of Roseto to be tested. The results were astonishing. Virtually no one under 55 died of a heart attack; for men over 65, the death rate from heart attack was half that of the United States as a whole; and the death rate from all causes was 35% lower than it should have been.

There was no suicide, no alcoholism, no drug addiction, and little crime to speak of. No one was on welfare and no one even suffered from peptic ulcers. These people died of old age. That’s it!

There was a name for a place like this – a place that lay outside everyday experience, where the normal rules did not apply. Roseto was an outlier.

The study concluded it was not diet related. The Rosetans Mediterranean diet was altered to some extent by the unavailability of products such as olive oil. Instead, the Rosetans cooked with lard, smoked heavily, and many struggled with obesity. The study also revealed that it wasn’t genetics and it wasn’t the specific location in Pennsylvania where Roseto was situated.

It was Roseto itself. They looked at how the Rosetans visited each other on a daily basis stopping to chat or cooking for each other in the backyard. Extended family clans were the norm, with three generations commonly living under the same roof. There was an enormous respect commanded by the grandparents who were part of the clan. They went to Mass and saw the calming and unifying effect of the church. There were 22 civic associations in a town of less than 2000 people. The Rosetans had created a social structure which insulated them from the pressures of the modern world. They were healthy because of where they were from and the world they had created for themselves.

The medical community had difficulty accepting these findings – no one was accustomed to thinking about health in terms of “location”. When the medical findings were presented, you can imagine the kind of skepticism they faced. Their findings could not be explained by long rows of data or complex charts referring to a kind of gene.

Instead, the findings talked about the mysterious and magical benefits of people talking to each other on the street and having three generations under one roof. Conventional wisdom explained a long life by looking at what people ate, how much they exercised, and how effectively they were treated by the medical system. Wolf’s findings required that he convince the medical establishment to think in an entirely new way. They had to look beyond the individual, to understand their culture, their friends, their families and what town in Italy their family came from. They had to appreciate their idea of community, their values, and the people with whom they surrounded themselves.